Political, social and economic problems amenable to the application of ‘systems thinking‘ are all around us. Take the Australian Prime Minister’s latest solution to the seemingly insoluble ‘boat people’ dilemma. ‘Boat people’ are refugees fleeing central or south east Asia who make their way to Indonesia, purchase passage from a ‘people smuggler’ to Australia on a leaky boat, only to find that the tub starts to take water somewhere near Christmas Island. What typically plays out next is a media-driven frenzy of political posturing and talk-back vitriol, while the Australian Navy scoops up the survivors and deposits them in a remote detention centre.

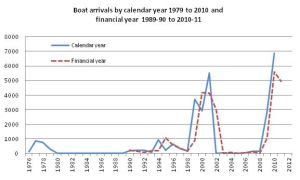

The scale of Australia’s border leakage problem is tiny compared with that of many other western countries. In the busiest years, the people smuggling trade moved around 5,000 customers. At the US-Mexico border, more prospective illegal immigrants die of exposure trying to make it to Texas each year. Australia’s illegal immigrant population is about 1/10th of that of the UK and the number of illegal residents in the USA is roughly equivalent to Australia’s population.

But the relative scale of the problem does nothing to comfort embarrassed Prime Ministers each time another sinking boat is reported. In 2001 the Howard conservative government set up remote on-shore and off-shore refugee ‘processing centres’. Over time, these have filled, and increasingly risk developing a Guantanamo-esque reputation. Prime Minister Rudd’s latest solution involves a deal with New Guinea to establish a new clearing house on Manus Island, 500km offshore from Madang. The PM talked of ‘breaking the people smuggler’s business model’ by guaranteeing that no refugee would set foot on Australian soil unless they could prove legitimate refugee status. However, it soon emerged that arrangements for returning or resettling others outside of Australia were hazy.

The problem certainly has elements of wickedness. There are no obvious solutions, and each potential intervention has undesirable or unintended consequences. The facts and drivers in the problem space are buried under layers of politicisation from all sides of the House. Further, the issue has taken new form as a moral and cultural sign-post — how we treat these people has become perceived as a very public reflection of national integrity.

The question of what is right is a moral one but with distinct constitutional, legal, policy, humanitarian, health and social dimensions. It challenges perceptions of Australian identity and motivates collective national reflection. Australians recognise the historical fact that we are a nation of immigrants, proudly anchored on egalitarianism and ‘a fair go for all’. But as the security bought by a century of relative isolation dissipates under new pressures from global economic, resource and climate trends, some immigrants to the Great Southern Land are feeling a little more equal than others.

The problem is laced with suggestions of sociopolitical systems and balances. Conundrums abound. Consider, for example, that Australia has publicly celebrated its multiculturalism and many have claimed a kind of hybrid vigour as a consequence in every field from politics to sport and art, so to turn its back on the most needy is tinged with hypocrisy. Next, as cited earlier, attempts to play down the relative importance of the problem (on the basis of international scale, for example) may be factual but do nothing to retard the rate of boat departures. Recognise that trying to regulate an underground market that spans jurisdictional and national borders or enforcing laws by catching and prosecuting the operators of the people smuggling businesses are, like the ‘war on drugs’, dubious and probably futile efforts. Not to mention that the economic impacts of such immigrants manifest indirectly and are difficult to measure, such as the cost to Australian society in terms of displacing Australian workers and becoming welfare-dependent, neither of which have much of a substantiated basis.

And while increasing deterrents to border-hopping may dissuade customers (refugees), it quickly nears humanitarian limits and results in domestic and international political heat. And as the Children Overboard and Tampa affairs proved, blaming refugees leads to humanitarian outrage, international condemnation and claims of demonization.

So how could systems thinking help? First and foremost, systems thinking provides lenses to view the complex and interrelated dimensions of the problem. Richard Veryard describes systems thinkers as conservative critics or realists, prone to taking alternative stances and seeing how an intervention may improve some feature of the political, social, or economic order, only to exacerbate other drivers of the problem.

Beyond a critical perspective, systems thinking approaches are increasing surfacing in a variety of guises, including ‘behavioural insights’ and business architecture. De Savigny and Adam apply systems thinking to health systems, a natural and needy domain, with the following general approach:

- Design the intervention by convening the right stakeholders, brainstorming interventions, conceptualising the effects (i.e. criticism), followed by adaptation and redesign as necessary

- Define what success looks like

- Design the evaluation by determining the right indicators, choosing evaluation methods, developing the evaluation mechanism and timeframe, setting a budget and sourcing funds

- Repeat 1. thru 3. until done (however that was defined).

Progress can be seen in what the authors call ‘major moments’ such as when leaders identify stakeholders, stakeholders convene, the design team forms, effects are conceptualised, etc. Although the approach does not advocate any reliance on the formalisms of Systems Thinking (such as Senge’s archetypes) it is tangible and pragmatic.

The systems thinking designer tackles enterprise-wide problems with some of the characteristics of Children Overboard or Tampa, although not the gravity. An overtly critical stance has value in recognising the systemic characteristics of the situation and in seeing through ill-conceived or naïve proposals. Beyond a pragmatic form of critical realism, methods like the one above should help.

Successive Australian governments have chosen the deterrent path resulting in over-scaled expenditures on processing centres and big publicity and media-handling efforts. Rudd’s quick-fire intervention is under attack as a political gesture that skirts around the nation’s humanitarian responsibilities and unilaterally offloads the resettlement problem onto neighbouring countries without their full consent. It is an intervention but not a solution. It raises almost as many problems it solves. And it is subject to the self-promotional, image-centric taint of a politician close to an election.

Perhaps his systems thinking advisors or policy architects were not adequately consulted. Or they may be actively pursuing the systems of public opinion through market research, focus groups and Facebook.

There is little cause and effect to be seen in a problem like people smuggling. A few days later, rescued refugees reportedly said that Rudd’s tougher stance would not have stopped them. That is the nature of the people smuggling sociopolitical system.